- Home

- Paula Guran [editor]

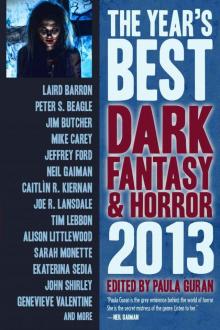

The Year's Best Dark Fantasy & Horror, 2013 Edition

The Year's Best Dark Fantasy & Horror, 2013 Edition Read online

THE YEAR’S BEST

DARK FANTASY AND HORROR

2013 EDITION

PAULA GURAN

For Navi—

Who currently makes my life and work both more bearable and, at times, more challenging.

Copyright © 2013 by Paula Guran.

Cover art by Andre Kiselev.

Cover design by Stephen H. Segal & Sherin Nicole.

Ebook design by Neil Clarke.

All stories are copyrighted to their respective authors, and used here with their permission.

ISBN: 978-1-60701-416-4 (ebook)

ISBN: 978-1-60701-396-6 (trade paperback)

PRIME BOOKS

www.prime-books.com

No portion of this book may be reproduced by any means, mechanical, electronic, or otherwise, without first obtaining the permission of the copyright holder.

For more information, contact Prime Books at [email protected].

Contents

Instructions for Use • Paula Guran

No Ghosts in London • Helen Marshall

Fake Plastic Trees • Caitlín R Kiernan

The Natural History of Autumn • Jeffrey Ford

Great-Grandmother in the Cellar • Peter S. Beagle

Renfrew’s Course • John Langan

End of White • Ekaterina Sedia

Who is Arvid Pekon? • Karin Tidbeck

Iphigenia in Aulis • Mike Carey

Slaughterhouse Blues • Tim Lebbon

England Under the White Witch • Theodora Goss

The Sea of Trees • Rachel Swirsky

The Man Who Forgot Ray Bradbury • Neil Gaiman

The Education of a Witch • Ellen Klages

Welcome to the Reptile House • Stephen Graham Jones

Glamour of Madness • Peter Bell

Bigfoot on Campus • Jim Butcher

Everything Must Go • Brooke Wonders

Nightside Eye • Terry Dowling

Escena de un Asesinato • Robert Hood

Good Hunting • Ken Liu

Go Home Again • Simon Strantzas

The Bird Country • K. M. Ferebee

Sinking Among Lilies • Cory Skerry

Down in the Valley • Joseph Bruchac

Armless Maidens of the American West • Genevieve Valentine

Blue Lace Agate • Sarah Monette

The Eyes of Water • Alison Littlewood

The Tall Grass • Joe R. Lansdale

Game • Maria Dahvana Headley

Pearls • Priya Sharma

Forget You • Marc Laidlaw

When Death Wakes Me to Myself • John Shirley

Dahlias • Melanie Tem

Bedtime Stories for Yasmin • Robert Shearman

Hand of Glory • Laird Barron

Acknowledgements

INSTRUCTIONS FOR USE

Paula Guran

A. Flip back a few pages or look at the cover. Note the words in the title: The Year’s Best.

Please be aware that a year’s best or best of the year or best new or some other variation on this phrase anthology (anthology, in this case, meaning: “a collection of selected literary pieces” published within a calendar year) cannot be taken to mean exactly what it says. It really means the book contains “some of the best of this type of short(ish) fiction as (a) found and read by, (b) within the personal definition of (insert type of fiction covered), (c) in consideration of certain factors of content as determined by, and (d) obtainable for reprint by the individual identified as the editor (not entirely without variables imposed by the publisher including, but not exclusively, how many pages) of said volume.” More or less.

The editors I know—and, I am fairly certain, those I don’t—who undertake these gigs take the responsibility very seriously. They strive to (a) give recognition to writers who have produced outstanding fiction and (b) offer readers some guidance, as well as (c) good value for their investment (in both time and money). Said editors work very hard to live up to the not exactly lofty honor (and seldom very remunerative) of being arbiters of excellence.

You may not always agree with their choices. That is your prerogative. Consider, debate, have your own opinion, but do not (a) condemn them for their definitions or their tastes, or (b) assume they believe their choices to be the only “bests.”

B. Now, consider the words: dark fantasy and horror.

Note: Both are highly debatable and constantly changing literary terms. So are labels like “science fiction,” speculative fiction,” “magic realism,” “surrealism,” “suspense thriller,” “mystery,” et cetera. Outside of the realm of the written word, the meaning of both are further confused, diluted, and twisted as they also are used to describe other media that convey stories to audiences.

Aforementioned “literary” and/or “genre” terms have been used/are used both correctly and incorrectly as marketing labels for various types of fiction and other media. Business is business. One cannot be a purest.

A dark fantasy or horror story might be only a bit unsettling or perhaps somewhat eerie. It might be revelatory or baffling. You might be “scared” or simply unsettled—or not. It can also simply be a small glimpse of life seen “through a glass, darkly.”

Darkness itself can be many things: nebulous, shadowy, tenebrous, mysterious, paradoxical (and thus illuminating) . . . and more.

Fantasy takes us out of our mundane world of consensual reality and gives us a glimpse or a larger revelation of the possibilities of the “impossible.”

Fantasy is sometimes, but far from always, rooted in myth and legend. (But then myths were once believed to be part of accepted reality. If one believes in the supernatural or the magical, is it still fantasy?) It also creates new mythologies for modern culture and this can affect us, become a part of who and what we are.

Horror is an affect. It is something we feel, an emotion. What we react to, respond to emotionally differs from individual to individual. In fact, to paraphrase those figures of legend, Sir Paul and Saint Lennon, we can’t tell you what we see when we turn out the light, but we know it is ours.

Horror is also about finding, even seeking, that which we do not know. When we encounter the unknowable we react with emotion. And the unknowable, the unthinkable need not be supernatural. We constantly confront it in real life.

In consideration of the above, I offer no definitions. I do offer you a diverse selection of dark fiction that I would call dark fantasy and/or horror all published within the calendar year 2012.

Elements of “the dark” and horror are increasingly found in modern stories that do not conform to established tropes. What was once mainstream or “literary” fiction frequently treads paths that once were reserved for “genre.” Stories of mystery and detection mixed with the supernatural are more popular today than ever and although they may also be amusing and adventurous, or have upbeat endings, that doesn’t mean such stories have not also taken the reader into stygian abysses along the why. Horror is also interwoven—essentially—into many science fiction themes. What post-apocalyptic fiction can be nothing but lightness and cheer? Ultimately, the reader may come away with a hopeful attitude, but not until after having to confront some very scary scenarios and face some very basic fears. Darkness seeps naturally into weird and surreal fiction too. The strange may be mixed with whimsy, but the fanciful does not negate the shadowy

The stories selected for this year often take twists and turns into the unexpected. Disquietude, disintegration, and loss (of many things, including one’s mind, memories, or love) evoke fear in some. Human treachery can be more terrifyi

ng than anything supernatural, or so strong it calls the unnatural into being. A deviant murderer’s monstrosity can go beyond the mere taking of a life, what is thought to be monstrous may not be at all, or monsters can wear the face of injustice. And, of course, we are often the monsters ourselves (or they live just next door.) The dead can be vengeful and terrifying, but they also find peace or help the living. A child’s world can be a frightening place, but then children can be quite frightening themselves.

These stories take us back to the past (be it historical, altered, or completely imagined), into a few futures, keep us in the present, and sometimes take us outside of time altogether. You’ll visit, among other places, China, Mexico, Russia, Japan, India, Scotland, an English country estate or two, and places that are not places at all.

Along the way, remember when we journey through the darkness, sometimes we emerge better for the journey—more alive, more knowing than when we embarked.

Or not.

C. Read, turn pages, consume.

D. Thanks.

Paula Guran

11 May 2013

National Twilight Zone Day

The dead cannot stay. They are decay, ruination. Things falling apart . . . But I will tell you a secret, a secret only I know . . .

NO GHOSTS IN LONDON

Helen Marshall

This is a sad story, best beloved, one of the few stories you don’t know, one of the few stories which I have kept to myself, locked up tight between cheek and tongue. Not a rainy-day story, no, not a bedtime story, but another kind of story: a sad story, as I said, but also a happy story, a story that is not all one thing at once and so, in the way of these things, a true story. And I have not told you one of those before. So hush up, and listen.

Gwendolyn had worked for the old manor house, Hardwick Hall, ever since her mum died. She knew all the stones in the manor house by heart, the ones kept rough and out of the reach of tourists, the ones smoothed by feet or hands, the uneven bits of the floor underneath the woven rush mat, the inward curves on the stairs; she knew the ghosts who had taken up residence in the abandoned upstairs rooms—dead sons and murdered lovers, a suicide or two, and the children who had died before reaching the age of ten. It was her home in many ways, the manor where her mum had worked. Her home. And though she longed to go off to university in the Great City of London, since childhood she had felt the Hall’s relentless drawstrings tugging tight as chain-iron around her. The kind, best beloved, that all young people feel in a place that is very, very old.

There was duty, of course. The old duchess’s bones creaked like a badly set floorboard when winter came to Derbyshire, and she was wary of strangers, wary of people since her brother’s sons had died in the war, wary of everyone except for the sad-eyed, long-jowled bulldog, Montague, who would sit by her side and snuffle against her ancient brocade skirt as she sewed. The duchess’s memory was moth-eaten with age, and the only faces that made sense to her were those that had been in her company for some time. As her mother had. As Gwendolyn had. And Gwendolyn found it easy to love the old woman, to love her pink-tongued companion. To love Hardwick Hall.

So there was love as well, which as we all know, best beloved, is as tight a drawstring as any. But love is not always happiness, particularly when you are young, and lovely, and just a bit lonely.

After she buried her mum in the spring in a ceremony that was sweet and sad and comforting with all the manor staff in attendance, Gwendolyn put on her mum’s apron and she tended the gardens and organized the servants, keeping them straight, letting them know there was still a firm hand about the place. Yes, my love, this is one of the sad bits but, hush, it was not so very sad as it might have been, for Gwendolyn had been loved by her mother very much, and, in the way of these things, that matters.

So. Gwendolyn stayed, and she minded the manor and all was well for the most part. The servants came to respect her, as they had her mum, to mind what she told them. The only people who didn’t attend to her properly were the ghosts. Oh, Gwendolyn would cajole, she would bribe, she would beg, she would order. But hers was a young face, and she was not a blood relation to them. She was a servant herself, and lacked, at that stage, a servant’s proper knowledge of how to subtly, secretly, put the screws to her master. Her mum had known how it was done—but her mum had kept many secrets to herself, as all mothers do, sure in the knowledge that there would be time later to pass them on.

Damien, the crinkle-eyed cowherd who minded the animals of the estate and drove the big tractor, the kind of man who was father and grandfather rolled into one, insisted that such things could not be forced. “Ghosts are an unruly lot,” he would say to her. “Can’t shift too much around at once. They’ll take a shine yet, bless.”

Shyly, Gwendolyn asked, “Will she ever . . . ?”

But she did not finish and Damien looked away as men do when they are sad and do not want to show it. Then he took her hand very carefully, as if it were one of the fine porcelain figures the duchess kept in her study. “I do not think so, love. Their kind”—meaning the ghosts, of course—“they stay for fear, or for anger, or for loneliness. Your mum, bless, she had none of that in her bones and too much of the other stuff. She’d have found somewhere better to rest herself, never you fear.”

Gwendolyn smiled a little, and she got on about the business of managing the place as best she could. But after a particularly bad day, when mad old William, the former count of Shrewsbury, had given her such a nasty shock that she had twisted her ankle on the uneven stairs, Gwendolyn decided enough was enough. It was one thing to have to deal with the tourists that filtered in every summer—they were strangers—but the ghosts were something closer to family. She missed her mum badly, but it was just too hard to shut herself away from a world glimpsed in strange accents and half-snatched conversations, a world enticing as any unknown thing is to a girl who lives among the dead, only to face the scorn and distemper of the closest thing to relatives she still had.

“I can’t abide it,” she confessed in a whisper to Damien as she cast her sad gaze over the roses clinging to the south wall of the garden where she had scattered her mother’s ashes. “They never acted up like this for mum.”

“Your mum, bless, she had more iron in her blood than the fifth cavalry had on their backs. Even those roses grow straighter and bloom brighter for fear of disappointing her.”

“I wish she were here,” Gwendolyn said.

“I know, love, I know.”

And so Gwendolyn packed her belongings into an old steamer trunk her mum had bought but never used, and she bid the duchess goodbye in the afternoon, as the sun slanted through the window into the blue room and lit up the silk trimmings so that they shone. Montague lay curled in a corner, breathlessly twitching in sleep, his tongue lolling like the edge of a bright pink ribbon. The duchess plucked at the needlework, fingers mindlessly unpicking what she had done, her only sign of agitation as she smiled a soft smile and bid Gwendolyn go. Then she cast her sad, milky eyes downwards, and patted Montague on the head with a kind of familiarity and gentleness that Gwendolyn never saw in the hurried, boisterous jostling of the tourists.

Gwendolyn did not look away then, though she desperately wanted to, because when you love someone, best beloved, and you know you will not see them again then, in the way of these things, you have to look.

Gwendolyn gritted her teeth and she looked until she couldn’t bear the weight of that ancient gaze any longer. Then she bent over, and kissed the old woman’s forehead, skin as light as brown paper wrapping, so that she could feel the hard bone of the skull underneath.

Then Gwendolyn turned, and in her turning something heavy seemed to fall away from her: the afternoon sun slanting through the window seemed full of hope and promise and if, here, it fell on only the aged, the dying and the dead and there, somewhere, it might also be falling upon things that glittered with their own newness. If she had been listening, Gwendolyn might have heard a whispered goodbye, and:

“Please, my darling, do not come back.” But with the sorry task of farewells done, Gwendolyn’s mind was already ten miles ahead of her feet.

London was the place she had seen in that afternoon-sun vision, a city sharp with hope, glass and steel glittering above streets paved with crisp-wrappers and concrete. She loved the cramped and smelly Tube ride, the tangle of lines that ran beneath the city, the curved cramped space where she would be crowded against men in clean-cut jackets, some slumped over so their backs curved along with the frame, girls dressed in leather, or chiffon, sitting demurely or hurling insults at one another with complete abandon. She loved the cluttered streets, the brown brick walls and white-trimmed windows. Everything was pressed so closely together she could put out both arms and touch the walls on either side of her dormitory room.

There were no ghosts in London, best beloved, not where the living took up so much space. Her roommate, Cindy—you wouldn’t like her, she was a lithe, long-legged girl from America who liked to wear heavy perfume and talk to her boyfriend in New York until ungodly hours of the morning—looked at her oddly when she spoke of them.

“We don’t have anything like that back home,” she’d say in a thick accent that seemed to misplace all the vowels and leave only the consonants in place. “In America, we like to get on with it, you know, lose the baggage.”

Gwendolyn liked the idea of getting on with it. Losing the baggage. She liked living without ghosts. She was a city girl now, a Londoner, a girl from London, and she gave herself to the city, let the city transform her the way all cities transform the people who inhabit them. She started wearing heavy perfume and putting on thick, black mascara that promised to give her THE LONDON LOOK, make her eyelashes—formerly stubby and mouse-brown like mine, yes, just like that—long and curving with 14X the volume. Like a movie star, Gwendolyn thought, staring at the fringe of it, the way it curled up away from her eyes in an altogether pleasing manner. She got herself a boyfriend, learned something about snogging, got herself another and learned something about the things that come after snogging.

The Year's Best Dark Fantasy & Horror, 2013 Edition

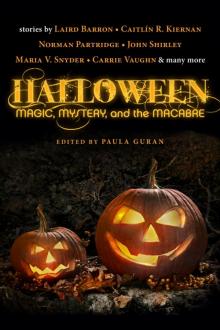

The Year's Best Dark Fantasy & Horror, 2013 Edition HALLOWEEN: Magic, Mystery, and the Macabre

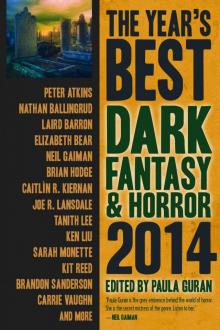

HALLOWEEN: Magic, Mystery, and the Macabre The Year's Best Dark Fantasy & Horror, 2014 Edition

The Year's Best Dark Fantasy & Horror, 2014 Edition