- Home

- Paula Guran [editor]

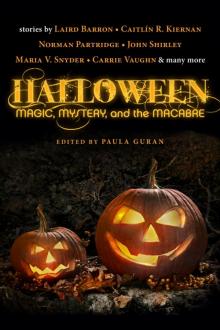

HALLOWEEN: Magic, Mystery, and the Macabre

HALLOWEEN: Magic, Mystery, and the Macabre Read online

HALLOWEEN

MAGIC, MYSTERY, AND THE MACABRE

PAULA GURAN

Again, for My Kids

May the magic of Halloween always be part of your lives.

Copyright © 2013 by Paula Guran.

Cover art by Sandra Cunningham.

Cover design by Sherin Nicole.

Ebook design by Neil Clarke.

All stories are copyrighted to their respective authors, and used here with their permission.

ISBN: 978-1-60701-418-8 (ebook)

ISBN: 978-1-60701-402-7 (trade paperback)

PRIME BOOKS

www.prime-books.com

No portion of this book may be reproduced by any means, mechanical, electronic, or otherwise, without first obtaining the permission of the copyright holder.

For more information, contact Prime Books at [email protected].

Contents

Introduction: New Boo • Paula Guran

Thirteen • Stephen Graham Jones

The Mummy's Heart • Norman Partridge

Unternehmen Werwolf • Carrie Vaughn

Lesser Fires • Steve Rasnic Tem & Melanie Tem

Long Way Home: A Pine Deep Story • Jonathan Maberry

Black Dog • Laird Barron

The Halloween Men • Maria V. Snyder

Pumpkin Head Escapes • Lawrence C. Connolly

Whilst the Night Rejoices Profound and Still • Caitlín R. Kiernan

For the Removal of Unwanted Guests • A. C. Wise

Angelic • Jay Caselberg

Quadruple Whammy • Chelsea Quinn Yarbro

We, The Fortunate Bereaved • Brian Hodge

All Hallows in the High Hills • Brenda Cooper

Trick or Treat • Nancy Kilpatrick

From Dust • Laura Bickle

All Souls Day • Barbara Roden

And When You Called Us We Came To You • John Shirley

About the Editor

Copyright Acknowledgements

INTRODUCTION: NEW BOO

Hark! Hark to the wind! ’Tis the night, they say,

When all souls come back from the far away—

The dead, forgotten this many a day!

—“Hallowe’en,” Virna Sheard

While researching and compiling the anthology Halloween, a treasury of reprinted stories published by Prime Books in 2011, I felt there was a need for some fresh tales for the old theme. Halloween: Magic, Mystery, and the Macabre is the result: eighteen new works of Halloween-inspired fiction. Happy Halloween!

Since I provided a lengthy essay about the holiday and its history as an introduction to Halloween, I won’t repeat myself here. (That introduction is available online here: www. prime-books.com/an-introduction-to-halloween.) But I will reiterate a few ideas pertinent to this volume.

Until fairly recently, we humans were much closer to nature and our lives far more dependent on the annual cycle of the seasons. For most of the northern hemisphere, autumn meant crops had to be harvested and stored, livestock slaughtered or secured for winter months. Survival during the upcoming darker colder days of winter must be considered and assured. But we couldn’t simply depend on nature, hard work, or even a bountiful harvest when it came to such matters of life-and-death; the season begat celebrations, ceremonies, rituals, religious beliefs, and the working of magic.

In Western European tradition—particularly that of the Celts—fall also marked one of the two times of the year (the other was the beginning of summer) when the mundane world was supposedly the closest to the “other world.” The friendly dead could commune and visit with the living; less-than-friendly supernatural entities could cause harm. Beloved souls traveled abroad, but so did fairies, vengeful ghosts, and malign spirits. One did one’s best to appease all.

Christianity gave the English language the word Hallowe’en sometime during the sixteenth century: a Scottish contraction of All Hallows’ Eve (evening)—the night before All Hallows’ Day, set by the Church on November 1. The “hallows” being the “hallowed”—the holy—commemorated on that feast day, also known as All Saints Day, The Feast of All Saints, and Solemnity of All Saints.

Long before the word was coined, however, Christianity’s efforts to dampen pagan belief in the extramundane had to be augmented to accommodate ideas that refused to disappear—concepts that are, perhaps, ingrained in our psyches. (After all, one of the defining elements of any religion is a belief in supernatural beings and forces. And most cultures develop mechanisms to help the living cope with the mystery of death.)

The connection with the dead and the supernatural was too powerful to be obliterated by merely honoring saints, so All Souls Day—also known as the Commemoration of All Faithful Departed—was established on November 2. The living could remember and pray for the souls of all the (Christian) dead; prayers offered for souls in Purgatory could alleviate some of their sufferings and help them reach heaven.

This was all well and good, but the older ways and beliefs persisted. Folks still believed the dead and supernatural beings wandered on All Hallows Eve; they were still—at least for that one night—part of the living world. Rituals and traditions were adapted . . . and continue to endure and evolve.

This—combined with other superstitions, bits of ancient and newer religions, different regional undertakings to prepare for winter and harvest, a hodgepodge of ethnic heritages, diverse cultural influences and practices, and various occult connections that seem always to be associated with the season—eventually became a celebration of otherness when scary things are acceptable, disguise is encouraged, and everyone can become anyone or anything they wish.

The season has always offered us an opportunity to consider or confront the coldest, darkest, deepest, most primal of our fears: death. In a multitude of ways the basic meaning of Halloween and the symbols and practices that have become associated with it—pranks, pumpkins, treats, bonfires, masks and costumes, the supernatural, the frightening, the fun—are ways of dealing with or even mocking that which comes to us all.

We might have faith or theory or hopes about what comes after death—a 2013 HuffPost/YouGov poll showed forty-five percent of American adults believe in ghosts, or that the spirits of dead people can come back in certain places and situations; sixty-four percent believe there’s a life after death. But no one really knows, do they?

Of course there’s always the chance that Halloween truly is a time when magic is possible, that forces beyond our ken are present, that the living and the dead can interact.

Magic, mystery, and the macabre—elements that inspire thoughts of the fantastic, the enchanting, the supernatural, the horrific, that which is not explainable, and so much more involved with the holiday. When soliciting stories for this anthology, I asked the writers keep that in mind. “Scary” was not necessarily the goal, but is a natural part of the mix. Nor did stories need to adhere to customs associated with the primarily North American Halloween as we know it today. Other—real or imagined—holidays and rituals that coincide with or parallel the Halloween season, or have connections to it could also be themes. Sometimes the fact that it is Halloween became the linchpin of a story.

The remarkable results are contained within. These tales are each a treat; no tricks involved, but there are certainly some very interesting twists. In Laird Barron’s “Black Dog,” a Halloween date in a whistle-stop town leads the protagonist far beyond its Catskills location. A small-town legend combines the sinister spells of a certain silver screen and Halloween in Stephen Graham Jones’s “Thirteen.” In Dunhaven, Brian Hodge’s isolated town of “We, the Fortunate Bereaved,” Halloween is a school ho

liday and genuine dark magic occurs on All Hallows Eve. Jonathan Maberry’s “Long Way Home” takes us back to his mysterious town of Pine Deep, Pennsylvania, on Halloween as a soldier returns from war. Brenda Cooper also re-visits a fictional site she previously introduced—a truly enchanting place on the other side that is more or less analogous to Laguna Beach, California—in “All Hallows in the High Hills.”

The season’s thin veil between the living and the dead is gently breached and a soul does some traveling in Melanie and Steve Rasnic Tem’s “Lesser Fires.” “Angelic” by Jay Caselberg also brings a family together for an annual get-together, but one fraught with far more meaning than one relative is aware. A strange multi-generational alliance in 1930s Kansas culminates with a Halloween harvest in Laura Bickle’s “From Dust.”

A modern witch copes with trust issues and Beggars’ Night in Nancy Kilpatrick’s “Trick or Treat.” Another witch manages some challenges of contemporary life by moving into a man’s new home—uninvited and accompanied by her cat—for the month leading up to All Hallows Eve in “For the Removal of Unwanted Guests” by A. C. Wise.

Both Norman Partridge and Carrie Vaughn take monsters whose popular tropes began in 1930s movies and are now connected to Halloween—the mummy and the werewolf—and add their own imaginative components: human trauma and psychosis in Partridge’s “The Mummy’s Heart,” and the World War II Nazi SS in Vaughn’s “Unternehmen Werwolf.” “Pumpkin Head Escapes” by Lawrence Connolly creates an entirely new boogeyman by combining theatrical and Halloween magic.

A visit to a haunted house unexpectedly takes the ghost hunters to a cemetery and a strange encounter in Barbara Roden’s “All Souls Day.” A hospital’s emergency room staff deals with Saturday night, the full moon, Halloween, and the weird in Chelsea Quinn Yarbro’s “Quadruple Whammy.”

In John Shirley’s “And When You Called Us We Came To You,” a young Chinese factory worker making products for the huge commercial U.S. Halloween market calls for aid from those who wait beyond the darkness, and they answer—thousands of miles away amid American teenagers. “Whilst the Night Rejoices Profound and Still” by Caitlín R. Kiernan takes us to a far future, another planet. and a strangely evolved festival with roots in our ancient celebration. Maria V. Snyder’s “The Halloween Men” are enforcers in a strange time and place far different than our own.

I’m sure that our All Hallows Eve brew will help make this a happy Halloween for those who consume it. With some luck—and maybe the casting of a magic spell or two—perhaps Halloween: Magic, Mystery, and the Macabre will become part of the season itself.

Paula Guran

Beltane 2013

THIRTEEN

Stephen Graham Jones

Here’s how you do it, if you’re brave enough.

First you go down to the Big Chief theater. That’s the old one behind the pizza place nobody goes to any more, the one my dad says he used to work at in high school, each of the ovens so deep, like a line of mouths to Hell.

The tops of his forearms have these smooth scars to prove it.

I’ve always wanted to write a word on that burned skin, then wait, see if it’s one of those prayers that make it through, get answered.

But this isn’t about him. This is about the Big Chief.

It’s just got two screens, and they’re right beside each other. If you’re in the first one and there’s a war movie in the second, you can hear the machine guns and dogfights and heroic last words bleeding through. It’s one big room, really, you can tell. They just hung a thick curtain right in the middle so they could show two movies, double their money.

My dream’s always been for them to roll that curtain up one night, show us the big picture.

Maybe someday.

It’s been there for forever, the Big Chief. According to Trino’s uncle, a kid got castrated there about fifteen years ago. In the last stall of the bathroom.

Maybe that’s why this trick works.

See, first you go there, get your ticket, your popcorn, and settle in. It doesn’t matter what row, or which theater, one or two. And if you’re watching a horror movie—it’s supposed to only work with horror movies—what you do is, right when it’s most scary, right when whoever’s with you is probably going to make fun of you for closing your eyes, you close your eyes. And hold your breath. And don’t let any sound in, kind of by humming all your thoughts into a dial tone.

And then you count two a hundred and twenty.

Two minutes, yeah.

That’s the real trick.

And if you’re getting scared, if you can feel it starting to work, you can breathe out all at once, even though you could have gone five or ten seconds longer.

It’s safest to do that, really.

Just breathe out, laugh, maybe hunch over into a coughing fit. Spilling your popcorn’s an especially good tactic, even—who would do that on purpose, right?

And then look back up to the screen through your tears. See that the movie’s still up there, right where it should be.

Your laugh’ll be kind of forced, but your smile, that’s a hundred percent true.

That’s where the movies should be, up on the screen.

If you make it to a hundred and twenty, though, then open your eyes?

The screen’ll look just exactly the same. And your friends’ll still be sitting there by you, waiting for you tell them what it was like. To see if it worked.

How it works is that, when you’re not looking, or listening, or breathing—it’s like how you’re supposed to hold your breath when your parents are driving by the cemetery. If you don’t, then you can accidentally breathe in a ghost.

That’s sort of how it works at the Big Chief.

With you not breathing, playing dead like you are, it makes like a road, or a door, and the movie seeps in. Way in the background, like at the edge of town, not everything changing all at once. Nothing that dramatic.

But the movie’s there. It’s there because you invited it. Because you left a crack it could come through, because you made a sound like a wish, and the darkness just washed that direction, to cover it up.

Ask Marcus Tider.

If you can talk to the dead, that is.

Marcus moved here last year, but he didn’t come to eighth grade with us in the fall. If all the girls’ collected hopes and dreams had anything to do with it, though, it would have been one of us in his place. Just so they could have him to take them on dates all through high school. Just so they could pin all their hopes and dreams on him, bat their eyes every time he passed, and then sigh into their lockers.

But Marcus—at his last school, it had been big, like 4A, and they’d been a rich district, the kind that has a pool. Meaning they had a swim team. And Marcus was too blond and too perfect not to have been captain.

He could hold his breath forever.

It was only a matter of time before he ended up at the Big Chief.

He wasn’t even scared of the movie, either, said horror was stupid, all make-believe. We were all there to watch, except for right at the end, when me and James ran out to the parking lot, to see if we could catch the movie starting, off on the horizon. Just see one star dimming out, another winking on.

There was nothing.

Inside—we heard later, had forgot our ticket stubs, couldn’t talk our way back in—Marcus just opened his eyes, looked around at everybody waiting for him to say how scary it had been.

He’d just shrugged, looked back up to the movie, and, like he’d timed it all out, that was when the monster lunged close to the camera, its tentacles whipping all around.

Everybody but Marcus flinched back into their seats.

City kids always think they know stuff we don’t, all the way out here. And maybe they do.

But we know some other things.

Two weeks later, we all figured he’d cheated somehow. That he’d peeked, or sneaked a breath using some swimmer trick. Or that he hadn’t believed right.

>

The Big Chief doesn’t care if you believe or not, though.

For Valentine’s Day four months later, Marcus threw blood up into his construction-papered shoe box, already floating with secret admirers.

None of us said anything.

He had a tumor inside him. Mr. Baker explained it in Life Science right before spring break. He hauled out the movie to show us, finally got the projector going, and when we saw it, that tumor, it was what we were already expecting: a tentacled monster, lashing out for whatever it could grab onto, pulling that bit of meat towards its center. But it could never get enough.

By Memorial Day, he was dead.

We sat in our back yards and ate the hamburgers and hot dogs our parents had grilled for us, and they didn’t ask us about Marcus.

His parents moved away for July fourth, their rearview sparking with the fireworks we felt compelled to light.

Their house is still empty.

And now that movie’s over.

This is a double-feature, though.

Marcus was just the example, the test case.

Grace, though.

Everybody loved Grace, me most of all. You know how when you know you’re going to grow up and marry somebody? That’s who she’d always been for me, all the way since fourth grade. I would have stepped in front of a truck for her. And I wouldn’t have closed my eyes, either.

We were supposed to have gone to homecoming together, but I got sick, then ended up locking the door to my room, my Exacto knife hovering over my stomach, because I’d been too close to the Big Chief that night Marcus held his breath, I knew. I had a tentacle monster inside me too.

I never cut deeper than a scratch, though.

My parents went on to homecoming without me—it had been their first date, fifty-thousand years ago—then knocked on my door when they got home, so I could knock back on my wall, and the next morning I was fine. Mom drove me over to Grace’s to give her the three-streamer corsage I’d been saving for since summer.

“There’ll be bumps in the road,” my mom said, pulling us away from Grace’s house. “You’ve just got to keep going, right?”

The Year's Best Dark Fantasy & Horror, 2013 Edition

The Year's Best Dark Fantasy & Horror, 2013 Edition HALLOWEEN: Magic, Mystery, and the Macabre

HALLOWEEN: Magic, Mystery, and the Macabre The Year's Best Dark Fantasy & Horror, 2014 Edition

The Year's Best Dark Fantasy & Horror, 2014 Edition